Commemorating Marbury v. Madison

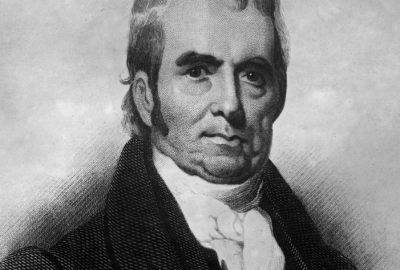

This month commemorates the 220th anniversary of one of the most important United States Supreme Court cases in the history of the United States, the landmark decision of Marbury v Madison, 5 U.S. 137, issued on February 24, 1803. Its author was Chief Justice John Marshall, who was only 47 years old at the time. He was appointed to the Court as Chief Justice only two years earlier by President John Adams, our second President from Quincy, Massachusetts. Chief Justice Marshall was the longest serving Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, serving for 34 years, from 1801 until his death on July 6, 1835, at the age of 79. Chief Justice Marshall is considered by many to be the greatest and most influential jurist to serve as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

One biographer of Chief Justice Marshall described Marbury v Madison as “the single most significant constitutional decision issued by any court in American history.” It was the first Supreme Court case that had declared an act of Congress unconstitutional, thus establishing the doctrine of judicial review, the foundation of our Federal constitutional law, and confirming the Supreme Court’s central role in interpreting the Constitution.

The issue directly presented in the case of Marbury v Madison was very minor. Plaintiff William Marbury was a successful banker and businessman from Georgetown, Maryland, who had actively campaigned for President Adams in the presidential election of 1800. The day before President Adams left office (having lost the election to his political rival, Thomas Jefferson) he appointed Marbury as a Justice of the Peace of Washington, D.C., a position that had a five-year term and drew no salary. The commission appointing Marbury was not delivered to him before Thomas Jefferson was inaugurated the next day as our third President. As President, Jefferson directed his Secretary of State, James Madison, to withhold several commissions issued by President Adams, including Marbury’s, because they had not been delivered before the change in administration. Marbury along with three other appointees filed suit against Madison in the Supreme Court seeking a writ of mandamus ordering Madison to deliver the parchment papers to them.

In its decision, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the commissions were valid once President Adams had signed them, finding that the delivery of the commissions was merely a ministerial act. Thus, Marbury and his three co-Plaintiffs technically won their case. However, the Court then held that it did not have the authority to issue the writ of mandamus that they had requested because the Act of Congress which gave the Supreme Court jurisdiction to hear this case and granted it the authority to issue the writ of mandamus conflicted with Article III of the Constitution which defined the limited scope of the Court’s original jurisdiction. Consequently, the Act of Congress was declared unconstitutional, and the Court could not validly issue the writ. This was a technical victory for President Jefferson.

Chief Justice Marshall deftly provided each party with a partial victory and masterfully avoided a conflict with the Jefferson administration, recognizing that the Supreme Court did not have any power to enforce the writ of mandamus should President Jefferson choose to ignore it. Far more significantly, Chief Justice Marshall held that the Supreme Court did have the authority to review and decide the constitutionality of the actions taken by the executive and legislative branches, thereby establishing the Court’s role as the final arbiter of the federal Constitution, with the authority to declare invalid any laws or actions enacted or taken by the President or Congress if in conflict with the federal Constitution. The doctrine of judicial review, which is not explicitly granted to the Court in the Constitution, established that the Court has the final say as to whether any laws or actions enacted or taken by Federal and State executive and legislative branches are unconstitutional, thereby establishing the authority of the Supreme Court to overrule the President, Congress, the States and all lower courts if its fair reading of the federal Constitution requires it. In the words of Chief Justice Marshall, “[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is… If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each.”

The power of judicial review gives the Supreme Court a crucial responsibility of assuring our individual rights and equal justice under the law.

The Supreme Court under Chief Justice Marshall never again declared an act of Congress unconstitutional. Portraits of William Marbury and James Madison hang together in the dining room of the Supreme Court.

© 2023 by Rich May, P.C. and Mark C. O’Connor. All rights reserved.